Next: Binary Classifiers Up: Fundamentals of Computer Vision Previous: LMedS

A predominant role in Computer Vision is played by Classification techniques and machine learning. The vast amount of information that can be extracted from a video sensor far exceeds the quantity that can be obtained from other sensors; however, it requires complex techniques that enable the exploitation of this wealth of information.

As previously mentioned, statistics, classification, and model fitting can be viewed as different facets of a single topic. Statistics seeks the most accurate Bayesian approach to extract the hidden parameters (of the state or model) of a system, potentially affected by noise, aiming to return the most probable output given the inputs. Meanwhile, classification offers techniques and methods for efficiently modeling the system. Finally, if the exact model underlying a physical system were known, any classification problem would reduce to an optimization problem. For these reasons, it is not straightforward to delineate where one topic ends and another begins.

The classification problem can be reduced to the task of deriving the parameters of a generic model that allows for generalization of the problem, given a limited number of examples.

A classifier can be viewed in two ways, depending on the type of information that the system aims to provide:

In the first case, a classifier is represented by a generic function

, composed of

, composed of  characteristics representing the example to be classified, confidence values regarding the possible

characteristics representing the example to be classified, confidence values regarding the possible

output classes (categories):

output classes (categories):

given the observed quantity

given the observed quantity  .

.

Due to the infinite nature of possible functions and the lack of additional specific information regarding the problem's structure, the function

is the output space,

is the output space,

is the input space, and

is the input space, and

are the model parameters

are the model parameters  to be determined during the training phase.

to be determined during the training phase.

The training phase is based on a set of examples (training set) consisting of pairs

To train the classifier, it is therefore necessary to identify the optimal parameters

It is generally not feasible to produce a complete training set: it is not always possible to obtain every type of input-output association in order to systematically map the entire input space to the output space. Even if this were possible, it would still be costly to have the memory required to represent such associations in the form of a Look Up Table. These are the main reasons for the use of models in classification.

The fact that the training set cannot cover all possible input-output combinations, combined with the generation of a model optimized for such incomplete data, can lead to a lack of generalization in the training: elements not present in the training set may be misclassified due to excessive adaptation to the training set (the overfitting problem). This phenomenon is typically caused by an optimization phase that focuses more on reducing the error on the outputs rather than on generalizing the problem.

Returning to the ways to visualize a classifier, it often proves simpler and more generalizable to directly derive from the input data a surface in

The expression (4.1) can always be converted into the form (4.2) through a majority voting process:

|

(4.3) |

The classifier, from this perspective, is a function that directly returns the symbol most similar to the provided input. The training set must now associate each input (each element of the space) with exactly one output class

If the function (4.1) indeed represents a transfer function, a response, the function (4.2) can be viewed as a partitioning of the space

For the reasons stated previously, it is physically impossible to achieve an optimal classifier (except for very small dimensional problems or for simple models that are perfectly known). However, there are several general purpose classifiers that can be considered sub-optimal depending on the problem and the required performance.

In the case of classifiers (4.2), the challenge is to obtain an optimal partitioning of the space; thus, a set of fast primitives is required that do not consume too much memory in the case of high values of

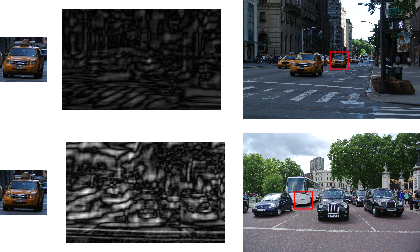

The information (features) that can be extracted from an image for classification purposes is manifold. Generally, using the grayscale/color values of the image directly is rarely employed in practical applications because such values are typically influenced by the scene's brightness and, most importantly, because they would represent a very large input space that is difficult to manage.

Therefore, it is essential to extract from the portion of the image to be classified the critical information (features) that best describes its appearance. For this reason, the entire theory presented in section 6 is widely used in machine learning.

Indeed, both Haar features are extensively utilized due to their extraction speed, and Histograms of Oriented Gradients (HOG, section 6.2) are favored for their accuracy. As a compromise and generalization between the two classes of features, Integral Channel Features (ICF, section 6.3) have recently been proposed.

To reduce the complexity of the classification problem, it can be divided into multiple layers to be addressed independently: the first layer transforms the input space into the feature space, while a second layer performs the actual classification starting from the feature space.

Under this consideration, classification techniques can be divided into three main categories:

Recently, techniques of Representation Learning constructed with multiple cascading layers (Deep Learning) have been very successful in solving complex classification problems.

Among the techniques for transforming the input space into the feature space, it is important to mention PCA, a linear unsupervised technique. The Principal Component Analysis (section 2.10.1) is a method that allows for the reduction of the number of inputs to the classifier by removing linearly dependent or irrelevant components, thereby reducing the dimensionality of the problem while striving to preserve as much information as possible.

Regarding the models and modeling techniques, widely used are:

|