Next: Soft Margin SVM Up: Classification Previous: LDA

LDA aims to maximize the statistical distance between classes but does not assess the actual margin of separation between them.

|

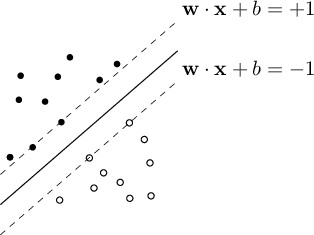

SVM (CV95), like LDA, allows for the creation of a linear classifier based on a discriminant function in the same form as shown in equation (4.5). However, SVM goes further: the optimal hyperplane in

Let us therefore define the classification classes typical of a binary problem in the form

Suppose there exist optimal parameters

samples provided during the training phase.

samples provided during the training phase.

It can be assumed that for each of the categories, there exists one or more vectors

The distance

To maximize the margin

This class of problems (minimization with constraints such as inequalities or primal optimization problem) is solved using the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker approach, which is the method of Lagrange multipliers generalized to inequalities. Through the KKT conditions, the Lagrangian function is obtained:

to be minimized in

From the nullification of the partial derivatives, we obtain:

By substituting these results (the primal variables) into the Lagrangian (4.21), it becomes a function of the multipliers only, the dual, from which the Wolfe dual form is derived:

and

and

. The maximum of the function

. The maximum of the function  evaluated over

evaluated over

corresponds to the

corresponds to the  associated with each training vector

associated with each training vector  . This maximum allows us to find the solution to the original problem.

. This maximum allows us to find the solution to the original problem.

In this relationship, the KKT conditions are valid, among which the constraint known as Complementary slackness is of considerable importance.

) or is a local minimum (

) or is a local minimum ( ). As a consequence, only the

). As a consequence, only the  on the boundary are non-zero and contribute to the solution: all other training samples are, in fact, irrelevant.

These vectors, associated with the

on the boundary are non-zero and contribute to the solution: all other training samples are, in fact, irrelevant.

These vectors, associated with the  , are the Support Vectors.

, are the Support Vectors.

By solving the quadratic problem (4.24), under the constraint (4.22) and

The most commonly used method to solve this QP problem is the Sequential Minimal Optimization (SMO). For a comprehensive discussion of the topics related to SVM, one can refer to (SS02).