PCA

Principal Component Analysis, or the discrete Karhunen-Loeve transform KLT, is a technique that has two significant applications in data analysis:

- it allows for the "ordering" of a vector distribution of data in such a way as to maximize its variance, and through this information, reduce the dimensionality of the problem: thus, it is a lossy data compression technique, or alternatively, a method to represent the same amount of information with fewer data;

- it transforms the input data such that the covariance matrix of the output data is diagonal, and consequently, the components of the data are uncorrelated with one another.

Similarly, there are two formulations of the PCA definition:

- it projects the data onto a lower-dimensional space such that the variance of the projected data is maximized;

- it projects the data onto a lower-dimensional space such that the distance between the point and its projection is minimized.

A practical example of dimensionality reduction is the equation of a hyperplane in  dimensions: there exists a basis of the space that transforms the equation of the plane, reducing it to

dimensions: there exists a basis of the space that transforms the equation of the plane, reducing it to  dimensions without losing information, thereby saving one dimension in the problem.

dimensions without losing information, thereby saving one dimension in the problem.

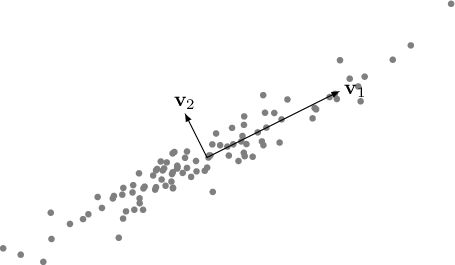

Figure 2.2:

Principal Components.

|

|

Let us consider

random vectors representing the outcomes of some experiment, realizations of a zero-mean random variable, which can be stored in the rows2.1 of the matrix

random vectors representing the outcomes of some experiment, realizations of a zero-mean random variable, which can be stored in the rows2.1 of the matrix  of dimensions

of dimensions  , which therefore stores

, which therefore stores  random vectors of dimensionality

random vectors of dimensionality  and with

and with  .

Each line corresponds to a different result

.

Each line corresponds to a different result  , and the distribution of these experiments must have a mean, at least the empirical one, equal to zero.

, and the distribution of these experiments must have a mean, at least the empirical one, equal to zero.

Assuming that the points have zero mean (which can always be achieved by simply subtracting the centroid), their covariance of occurrences  is given by

is given by

|

(2.66) |

.

If the input data  are correlated, the covariance matrix

are correlated, the covariance matrix

is not a diagonal matrix.

is not a diagonal matrix.

The objective of PCA is to find an optimal transformation  that transforms the correlated data into uncorrelated data

that transforms the correlated data into uncorrelated data

|

(2.67) |

and arranged according to their informational content in such a way that, by selecting a subset of the bases, this approach can reduce the dimensionality of the problem.

If there exists an orthonormal basis  such that the covariance matrix of

such that the covariance matrix of

expressed in this basis is diagonal, then the axes of this new basis are referred to as the principal components of

expressed in this basis is diagonal, then the axes of this new basis are referred to as the principal components of

(or of the distribution of

(or of the distribution of  ). When a covariance matrix is obtained where all elements are

). When a covariance matrix is obtained where all elements are  except for those on the diagonal, it indicates that under this new basis of the space, the events are uncorrelated with each other.

except for those on the diagonal, it indicates that under this new basis of the space, the events are uncorrelated with each other.

This transformation can be found by solving an eigenvalue problem: it can indeed be demonstrated that the elements of the diagonal correlation matrix must be the eigenvalues of  , and for this reason, the variances of the projection of the vector

, and for this reason, the variances of the projection of the vector  onto the principal components are the eigenvalues themselves:

onto the principal components are the eigenvalues themselves:

|

(2.68) |

where  is the matrix of eigenvectors (orthogonal matrix

is the matrix of eigenvectors (orthogonal matrix

) and

) and

is the diagonal matrix of eigenvalues

is the diagonal matrix of eigenvalues

.

.

To achieve this result, there are two approaches. Since

is a symmetric, real, positive definite matrix, it can be decomposed into

is a symmetric, real, positive definite matrix, it can be decomposed into

|

(2.69) |

, referred to as the spectral decomposition, with  being an orthonormal matrix, the right eigenvalues of

being an orthonormal matrix, the right eigenvalues of

, and

, and

is the diagonal matrix containing the eigenvalues. Since the matrix

is the diagonal matrix containing the eigenvalues. Since the matrix

is positive definite, all eigenvalues will be positive or zero. By multiplying the equation (2.69) on the right by

is positive definite, all eigenvalues will be positive or zero. By multiplying the equation (2.69) on the right by  , it is shown that it is indeed the solution to the problem (2.68).

, it is shown that it is indeed the solution to the problem (2.68).

This technique, however, requires the explicit computation of

. Given a rectangular matrix

. Given a rectangular matrix  , the SVD technique allows us to precisely find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the matrix

, the SVD technique allows us to precisely find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the matrix

, that is, of

, that is, of

, and therefore it is the most efficient and numerically stable method to achieve this result.

, and therefore it is the most efficient and numerically stable method to achieve this result.

Through the SVD, it is possible to decompose the event matrix  such that

such that

using the Economy/Compact SVD representation where  are the left singular vectors,

are the left singular vectors,  are the eigenvalues of

are the eigenvalues of

, and

, and  are the right singular vectors.

are the right singular vectors.

It is noteworthy that using the SVD, it is not necessary to explicitly compute the covariance matrix

. However, this matrix can be derived later through the equation

. However, this matrix can be derived later through the equation

|

(2.70) |

.

By comparing this relation with that of equation (2.69), it can also be concluded that

.

.

It is important to remember the properties of eigenvalues:

- The eigenvalues of

and

and

are the same.

are the same.

- The singular values are the eigenvalues of the matrix

, which is the covariance matrix;

, which is the covariance matrix;

- The largest eigenvalues are associated with the direction vectors of maximum variance;

and also an important property of the SVD

|

(2.71) |

which is the rank  approximation closest to

approximation closest to  . This fact, combined with the inherent characteristic of SVD to return the singular values of

. This fact, combined with the inherent characteristic of SVD to return the singular values of  ordered from largest to smallest, allows for the approximation of a matrix to one of lower rank.

ordered from largest to smallest, allows for the approximation of a matrix to one of lower rank.

By selecting the number of eigenvectors with sufficiently large eigenvalues, it is possible to create an orthonormal basis  of the space

of the space

such that

such that

obtained as a projection

obtained as a projection

represents a reduced-dimensional space that still contains most of the information of the system.

Figure 2.3:

Example of the first 10 eigenvectors  extracted from the Daimler-DB pedestrian dataset

extracted from the Daimler-DB pedestrian dataset

|

|

Footnotes

- 2.1

- In this document, the convention for rows has been chosen: in the literature, one can find both row and column representations of data, and consequently, the nomenclature might differ, referring to

instead of

instead of  and vice versa.

and vice versa.

Paolo medici

2025-10-22

are correlated, the covariance matrix

are correlated, the covariance matrix

is not a diagonal matrix.

is not a diagonal matrix.

is the matrix of eigenvectors (orthogonal matrix

is the matrix of eigenvectors (orthogonal matrix

) and

) and

is the diagonal matrix of eigenvalues

is the diagonal matrix of eigenvalues

.

.

being an orthonormal matrix, the right eigenvalues of

being an orthonormal matrix, the right eigenvalues of

, and

, and

is the diagonal matrix containing the eigenvalues. Since the matrix

is the diagonal matrix containing the eigenvalues. Since the matrix

is positive definite, all eigenvalues will be positive or zero. By multiplying the equation (2.69) on the right by

is positive definite, all eigenvalues will be positive or zero. By multiplying the equation (2.69) on the right by  , it is shown that it is indeed the solution to the problem (2.68).

, it is shown that it is indeed the solution to the problem (2.68).

are the left singular vectors,

are the left singular vectors,  are the eigenvalues of

are the eigenvalues of

, and

, and  are the right singular vectors.

are the right singular vectors.

and

and

are the same.

are the same.

, which is the covariance matrix;

, which is the covariance matrix;

approximation closest to

approximation closest to  . This fact, combined with the inherent characteristic of SVD to return the singular values of

. This fact, combined with the inherent characteristic of SVD to return the singular values of  ordered from largest to smallest, allows for the approximation of a matrix to one of lower rank.

ordered from largest to smallest, allows for the approximation of a matrix to one of lower rank.

instead of

instead of  and vice versa.

and vice versa.