Next: Lens Distortion Up: Fundamentals of Computer Vision Previous: Lucas-Kanade

In this chapter, we address the problem of describing the process through which incident light on objects is captured by a digital sensor. This concept is fundamental in image processing as it provides the relationship that connects the points of an image with their position in the world, allowing us to determine the area of the world associated with a pixel of the image or, conversely, to identify the portion of the image that corresponds to a specific region in world coordinates.

The universally accepted projective model, known as the Pin-Hole Camera, is based on simple geometric relationships8.1.

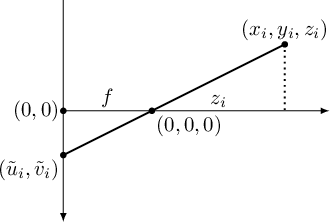

In figure 8.1, a highly simplified diagram illustrates how the image is formed on the sensor. The observed point

|

Analyzing figure 8.1, it can be observed that the ratios between similar triangles generated by optical rays describe the equation that allows projecting a generic point

is the focal length (the distance between the pin-hole and the sensor). It should be noted that the coordinates

is the focal length (the distance between the pin-hole and the sensor). It should be noted that the coordinates

, expressed in camera coordinates, in this book follow the left-hand rule (commonly used in computer graphics), as opposed to the right-hand rule (more commonly used in robotic applications), which is chosen to express world coordinates. The use of coordinate

, expressed in camera coordinates, in this book follow the left-hand rule (commonly used in computer graphics), as opposed to the right-hand rule (more commonly used in robotic applications), which is chosen to express world coordinates. The use of coordinate  to express distance is a purely mathematical requirement due to the transformations that will be presented shortly.

to express distance is a purely mathematical requirement due to the transformations that will be presented shortly.

The sensor coordinates

(principal point) account for the offset of the origin of the coordinates in the stored image relative to the projection of the focal point onto the sensor.

(principal point) account for the offset of the origin of the coordinates in the stored image relative to the projection of the focal point onto the sensor.

In the absence of information available from the various datasheets regarding

and

and  angles that can be approximated to the half-angle of the camera aperture (horizontal and vertical, respectively).

When the optics are undistorted and the sensor has square pixels,

angles that can be approximated to the half-angle of the camera aperture (horizontal and vertical, respectively).

When the optics are undistorted and the sensor has square pixels,  and

and  tend to take on the same value.

tend to take on the same value.

Due to the presence of the ratio, the equation (8.1) cannot be clearly represented in a linear system. However, it is possible to modify this representation by adding an unknown

Using homogeneous coordinates, it can be easily shown that the system (8.1) can be written as

. For this reason,

. For this reason,  is implied, and instead, homogeneous coordinates are used: to obtain the point in non-homogeneous coordinates, one must divide the first two coordinates by the third, resulting in equation (8.1).

The use of homogeneous coordinates allows for the implicit representation of division by the coordinate

is implied, and instead, homogeneous coordinates are used: to obtain the point in non-homogeneous coordinates, one must divide the first two coordinates by the third, resulting in equation (8.1).

The use of homogeneous coordinates allows for the implicit representation of division by the coordinate  .

.

The matrix

Such a matrix, not depending, as we will see later, on factors other than those of the chamber itself, is referred to as the matrix of intrinsic factors. The matrix

With modern digital sensors and the construction of cameras not manually but with precise numerical control machines, it is possible to set the skew factor

Setting

The knowledge of these parameters (see section 8.5 regarding calibration) determines the ability to transform a point from camera coordinates to image coordinates or, conversely, to generate the line in camera coordinates corresponding to a point in the image.

With this modeling, in any case, the contributions due to lens distortion have not been taken into account. The pin-hole camera model is indeed valid only if the image coordinates used refer to undistorted images.