Next: Tait-Bryan Angles Up: Fundamentals of Computer Vision Previous: 2D Gaussian Splattering

|

Rotations are isometric transformations of Euclidean space, meaning they transform vectors while preserving their length and leave a set of points unchanged in space, corresponding to a hyperplane (the center of rotation in the two-dimensional case or an axis of rotation in the three-dimensional case).

The set of all Rotation Matrices

|

(A.1) |

.

.

There are two possible conventions for defining a rotation matrix: some authors prefer to write the matrix that transforms from sensor coordinates to world coordinates, while others prefer the opposite. The rotation matrix itself serves a dual purpose: it can indicate a rotation within a reference frame (Active or Alibi), or it can represent the transformation of coordinates from one reference frame to a second reference frame (Passive or Alias).

In this book, matrices are primarily used to represent changes of basis, and whenever possible, the source and destination reference systems are clearly highlighted.

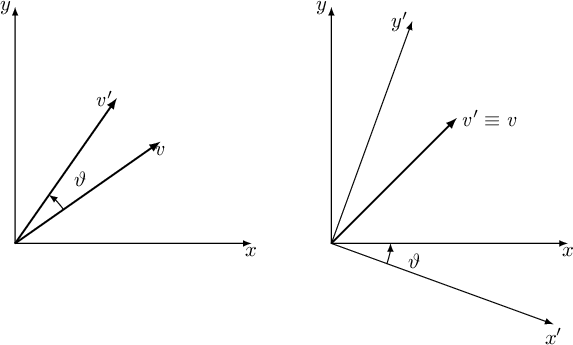

To discuss rotation matrices and make some interesting observations, it is convenient to start by analyzing the two-dimensional case, as illustrated in Figure A.1.

It can be verified that

As can be seen from Figure A.1, when discussing a rotation by an angle

The distinction between Inner/Active/Alibi Transformation and Outer/Passive/Alias Transformation is another way to describe the difference between rotations. These terms are often used in mathematical and physical contexts to clarify whether a transformation acts on the reference frame itself (the reference frame is rotated or translated while the objects remain fixed in space, hence alias or passive) or on the objects within a fixed reference frame (the objects are rotated or translated while the reference frame remains unchanged, hence alibi or active).

The rotation matrix is also referred to as the Direction Cosine Matrix (DCM) because the columns of the transformation matrix correspond to the matrices of the coefficients of the old basis vectors expressed in terms of the new basis.

In this book, by working primarily with sensors (rather than robotic arms), all matrices are effectively change of basis matrices, as the main objective is to determine the coordinates of a point as perceived by a sensor in the higher reference frame, or vice versa.

Transitioning to the three-dimensional case complicates matters further: there are infinite parametrizations to express a rotation starting from 3 parameters

A rotation can be defined, for instance, as a composition of three elementary rotations around one of the three axes. However, since matrix multiplication is non-commutative, there are 24 distinct ways to combine these three matrices. The combinations of matrices are referred to as Euler sequences, followed by three numbers indicating the order of combination of the rotations: 1 for the axis

In robotics, the representation of Euler angles (sequence ZYZ) or Tait-Bryan angles (Euler sequence 321 or ZYX) is widely used; see the following section A.1 for detailsA.2. In Italian literature, the six groups (XYZ, YZX, ZXY, XZY, ZYX, YXZ) are referred to as Cardano angles.

However, this system of angles presents some singularities that limit its use. Alternatively, the syntax proposed by Rodrigues (section A.2) or quaternions (section A.3) can be employed to overcome this issue.

Due to the non-commutative nature of matrix multiplication, there is an additional level of ambiguity in three-dimensional space stemming from the order in which Euler angles are described, as rotations can be defined as extrinsic or intrinsic:

An extrinsic rotation is equivalent to an intrinsic rotation (and vice versa) but with the order of composition of the transformations reversed (e.g., an extrinsic transformation z-y-x is equivalent to an intrinsic transformation x-y'-z”).

Regardless of the geometric interpretation assigned to the rotation matrix, it is still possible to make several observations.

As previously mentioned, the definition of the matrix

Deriving an expression for the matrix

Let us consider a generic rotation

Since the camera/image reference system is a Left-Bottom-Front system (with X increasing to the right, Y increasing downward, and Z representing depth as shown in figure 8.3), which differs from the Front-Left-Up sensor/world reference system (with Z increasing upward, X representing depth, and Y increasing to the left as illustrated in figure 8.4), it is necessary to define a matrix

When working in the aerospace or naval fields, it may be necessary to transition from a camera/image system to a Front-Right-Down system (for example, the NED). In this situation, the permutation matrix is

Under these considerations, the matrix

, may be referred to in the literature as the "rotation matrix" and is also denoted by the letter

, may be referred to in the literature as the "rotation matrix" and is also denoted by the letter  .

.